Pandemic-Driven Changes at the Front Lines of Medical Education: FITs Respond to COVID-19

Fellows in Training (FITs) and medical residents are an integral part of responses to medical catastrophes. Medical trainees have a unique perspective of patient care from the front lines, and often work shoulder-to-shoulder with other essential medical personnel.

During the Boston Marathon Bombing, residents and fellows responded alongside faculty, providing Boston training programs with the impetus to incorporate disaster management principles into their formal curricula.

In March 2020, before the number of worldwide infections had skyrocketed to nearly 2 million cases, the virus known as SARS-CoV-2 had infected more than 100,000 of the world's population and reached pandemic proportions.

Hospitals worldwide, including China, Italy and Washington State, were unprepared for COVID-19. Medical schools in Italy began to fast-track medical students to graduation in order to assist the overburdened physician workforce.

During this time, a group of cardiology FITs at Johns Hopkins Hospital attempted to prepare for the onset of the pandemic within Baltimore.

To improve the safety of clinical work, sustain well-being and organize a practical disaster management curriculum for FITs, we implemented a multifaceted approach including: 1) assessment of FIT needs and perspectives, 2) a unified call to action and 3) changes in response to COVID-19.

We hope that our response to COVID-19 may serve as an example of the role of trainees during critical health care challenges.

Assessing FIT Needs and Experiences

With each passing day, the pandemic placed a strain upon the hospital and its trainees. The hospital's full cohort of cardiology fellows and faculty faced continued risk of viral transmission. As numbers of infected COVID-19 patients grew, the first challenge was high demand for personal protective equipment (PPE).

Limited testing posed another barrier to health and safety of trainees, as testing for SARS-CoV-2 was only accessible during limited daytime hours of occupational health services. At times, trainees struggled to access basic necessities including food and cleaning supplies.

We wanted an opportunity to gather FIT perspectives, unify these voices and contribute to a response against the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Therefore, we aimed to identify both the magnitude and granular details of challenges faced by health care workers.

Through a survey released on March 15 to cardiology fellows and medicine residents within Johns Hopkins Medicine, we endeavored to understand the needs and perspectives of trainees at the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Survey topics included FIT concerns regarding COVID-19, PPE and personal well-being. Trainees were asked directly, "What new policies should we implement to address our clinical response to COVID-19?"

Within 24 hours, 31 cardiology fellows and 51 internal medicine residents completed the survey (n=82), corresponding to a survey completion rate of 42% overall, 67% for fellows and 35% for residents.

A Call to Action

We aimed to form an integrated, goal-directed response using survey results. Although individual responses to the survey relayed challenges and anxiety, when combined these responses carried common themes, showing that each trainee is not alone.

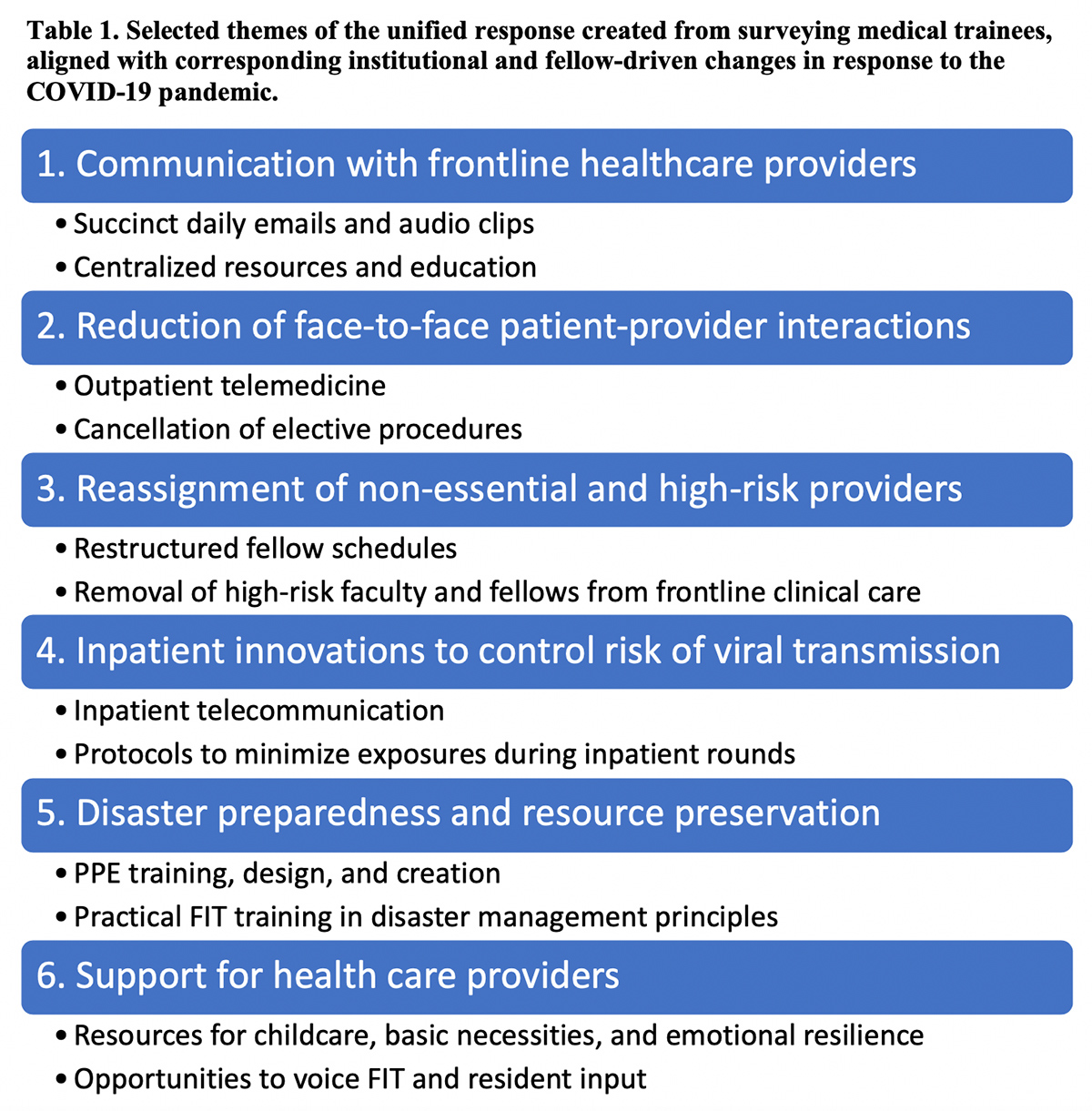

Moreover, trainees suggested creative ideas and plans to implement changes at many levels. Our collective response was a call to action, emphasizing six major changes (Table 1).

First, trainees requested increased communication with health care providers. Only 25% of all trainees knew the location of the containment area and the number of admitted COVID-19 patients.

Ninety-six percent of responders requested regular updates regarding currently infected staff and patients. More than 50% of survey participants suggested compilation of a single online resource with clearly labeled categories of high-yield information.

Second, to reduce risk of viral transmission, trainees asked to minimize provider interactions with clinically stable patients and hospital visitors. Ninety-five percent of survey responders agreed that both nonurgent clinic visits and nonurgent procedures must be canceled.

Cardiology FITs discussed telemedicine and the nuances of triaging urgent and nonurgent cardiac procedures. Residents suggested use of drive-through testing sites and restriction of hospital visitors.

Third, trainees requested to minimize patient interactions with nonessential and high-risk staff. Eighty-seven percent of cardiology responders asked to skeletonize inpatient staff in order to make more resources available.

Trainees suggested a well-defined jeopardy backup system and outpatient assistance of inpatient providers through remote support. Eighty percent of trainees requested that providers with comorbidities be removed from clinical care.

Fourth, trainees asked to change inpatient practices, including testing, PPE and rounding. Sixty-one percent of trainees requested to expand testing for COVID-19 to include all patients with respiratory symptoms, 33% of trainees requested to expand testing to include all inpatients and health care workers, and 35% of trainees were confused about the current restrictions to testing.

FITs and residents focused many concerns upon guidelines, availability and supply plan for PPE. Twenty different trainees described difficulty obtaining hospital-mandated PPE, and even more anticipated running out during their clinical service. Eighty percent of survey responders asked for additional PPE training resources, including 30% who wanted in-person PPE training.

Trainees also suggested changing inpatient rounding practices. Seventy-two percent of responders wanted to eliminate team rounds involving in-room teaching and presentations. Overall, FITs suggested changing inpatient practices to increase PPE and limit superfluous face-to-face patient interactions.

Fifth, trainees posed insightful questions regarding disaster preparedness and resource preservation. Many suggested diverse strategies for organizing quarantine units, adequate ventilator capacity, access to COVID-19 drug trials, jeopardy schedules, support for environmental and cleaning departments, and supply-lines for PPE.

Sixth, trainees emphasized that more support for health care providers is needed both in and out of the hospital. Thirty-seven percent of trainees reported that they did not have adequate home cleaning and food supplies, and requested support from Graduate Medical Education (GME) to meet these needs.

Twenty-three percent of polled residents and fellows reported that they did not have adequate childcare support; some posed solutions such as community initiatives for group childcare support.

Many trainees described anxiety and isolation, and suggested resources providing social and emotional support. Others requested that GME destigmatize symptom reporting, mask use and other measures to prevent spread of SARS-CoV-2.

Making Changes

We shared the survey results, including unifying themes (Table 1) and trainee suggestions for COVID-19, with trainees as well as leadership within cardiology, medicine and GME on March 16. In the upcoming week, Johns Hopkins Hospital witnessed a number of changes including volunteer recruitment for surge coverage, expanded PPE training and outpatient telemedicine.

Throughout the pandemic, Johns Hopkins leadership has acted swiftly, and many institutional changes were planned independently of FIT survey responses. However, three considerations rendered the survey results valuable to the institution. First, trainees answered the survey without knowledge of upcoming administrative changes.

The survey thus provided a practical lesson in disaster preparedness for trainees, with real-time feedback in the form of new policies that coincided with trainee suggestions.

Second, many trainees were grateful for the survey; they reported increased camaraderie and morale after they were called upon to share their thoughts.

Third, survey responses provided leadership with information regarding the needs of first responders. For example, GME provided additional wellness resources while armed with survey information regarding the magnitude of barriers to food and childcare.

A core group of our FITs has additionally innovated fellow-driven changes in response to the pandemic. Our chief fellow and program director restructured the fellowship schedule to reduce on-site staffing from 14 to 4 inpatient fellows and rescheduled fellows with higher risk of serious COVID-19 complications.

FITs on service reduced contact between inpatients and staff by facilitating inpatient iPAD-based telemedicine communication with patients under isolation, reducing excess labs and vitals, changing rounding structures to limit time and staff inside patient rooms, and designing additional PPE for colleagues.

FITs also supported faculty through the division's transition to outpatient telemedicine. To communicate succinctly and boost morale, FITs produced a daily five-minute audio update for the entire cardiology division.

To increase fellow education, FITs formed a centralized COVID-19 information hub which summarized and shared COVID-19 information with colleagues locally and internationally.

Overall, both institutional and fellow-driven changes have aligned with overarching themes of the initial FIT survey including communication, reduction of face-to-face interactions, resource preservation and support for health care providers.

Our response to COVID-19 as FITs began by gathering the perspectives of trainees and continues with an ongoing effort to make practical changes that reflect the voices of FITs and residents as a whole.

Conclusions

Trainees have played a role in the clinical response to the COVID-19 pandemic by assessing needs, advocating for change, finding and implementing solutions, and caring for patients at the front lines.

The thoughts of our fellows and residents not only reflect a health care system's daily reality, but also highlight potential solutions. In any fluid situation requiring innovation and rapid reassessment, the voice of trainees may be harnessed when moving a health care system toward positive changes.

This pandemic will shape the way we practice medicine for decades to come. Young doctors will be responsible for sharing their experiences in disaster preparedness with future generations.

Beyond what we learn from a clinical and epidemiologic perspective, key lessons will include communicating transparently, supporting each other, fulfilling our responsibility to care for patients, addressing our own needs, adapting both quickly and creatively, and valuing trainees as an integral component of our response.

Acknowledgements

The following individuals were instrumental to Johns Hopkins Cardiology fellowship's early COVID-19 response: Dr. Eunice Yang and Dr. Steven Schulman for program leadership and curriculum restructuring; Dr. Anum Minhas, Dr. Nino Isakadze, and Dr. Nick Smith for inpatient medicine changes; Dr. Daniel Ambinder, Dr. Carine Hamo, and Dr. Jacqueline Latina for communications and medical education; and Dr. Paul Scheel for telemedicine. Thanks to the Division of Cardiology for offering fellows the opportunity to participate in the institution's COVID-19 response, and to Dr. Garima Sharma for mentorship.